This is a guest article written by Ms. Sunita Sanghi, Ex. Principal Adviser, Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE) and Dr. Gagan Preet Kaur, Urban Skilling Specialist, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs.

India is one of the youngest nations in the world with more than 62% of its population in the working-age group (15-59 years), and over 54% of its total population below 25 years of age. Its population pyramid is expected to “bulge” across the 15–59 age group over the next decade.

To reap this demographic dividend, India needs to equip its workforce with employable skills and knowledge so that they can contribute substantively to the economic growth of the country. The need of the hour is to align training with the needs of the industry while understanding the needs/aspirations of the youth.

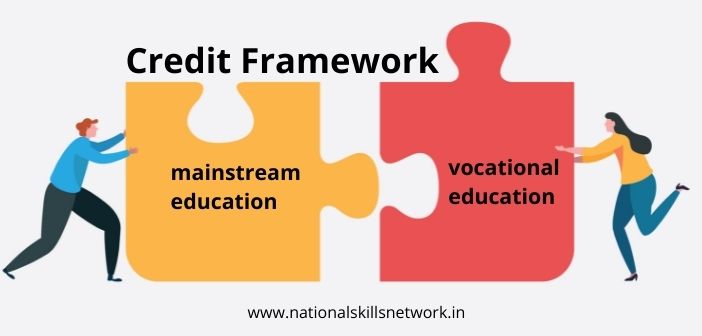

Currently, vocational education is perceived to be inferior to mainstream education. However, this concern can be dealt with re-imagination of how vocational education is offered to students in the future. The National Education Policy 2020 (NEP 2020) lays stress on the integration of formal education with vocational education at all levels in a long way.

The key building blocks for this integration includes

Credit framework

Standardizing qualifications by aligning with National Skill Qualification Framework (NSQF)

Continuous improvement in the curriculum

Training of Trainers

Alignment with industry needs

This article focuses on establishing equivalence and mobility between vocational education and general education through a credit framework.

Need for Credit Framework

The National Education Policy 2020 gives impetus to credit-based courses for holistic and multidisciplinary learning. The policy focuses on principles such as learning by doing value-based and multidisciplinary education through local industry internships, research internships, community engagement, etc.

While choosing courses based on local opportunities and skill gap surveys, academic institutions are to collaborate with ITIs, Polytechnics, Local Businesses, NGOs, etc. The NEP 2020 not only envisages exposure to vocational education from the upper primary level with experiential learning but also proposes vocational education expansion through NIOS for those youth who are not able to attend physically.

It is seen that many youth who drop out of the education system, either enter the labour market without training or may undergo short-term training. Given this fact, it is important to ensure that vocational and academic education are interlinked with provisions for mobility with vocational education, vocational to academic and vice versa with suitable credits for prior experience. Accordingly, vocational courses offered in schools can be mapped to ITIs, B. Voc and higher education institutions under NSQF so that weightage could be given to students for entering higher-level vocational education to ensure vertical mobility.

A credit framework for vocational education will –

- Help people convert learning to recognizable skills to ensure them movement in their career

- Aid in breaking the myopic perception that short-term courses are standalone/ dead-end courses with no well-defined linkages either with long term qualifications within vocational education framework and any equivalence with the general education.

While facilitating mobility between vocational and formal education, the credit system through the transfer of credit will –

- Enable the learner to drop a subject already studied or take the next level course in that subject

- Seek direct admission to higher-level such as direct second-year admission, etc.

The credit system would facilitate multiple entry and exit and facilitate the persons with prior experience and undergoing RPL mobility in their career.

However, it is important to identify components of the credit framework; mechanisms for assigning and accumulating credits across various forms of education covering a large number of boards and university ecosystems so as to ensure seamless mobility across academic and vocational education.

Given this premise, it becomes imperative to establish and formalize a system of credit allocation; accumulation and transfer not only within the skill development ecosystem but also with forward linkages to academic education.

Therefore, the most important task is to define what constitutes credit and what could be its potential unit given the differences in academic and vocational education. The number of credits may be worked out on the basis of the number of notional learning hours that an average learner at a specified NSQF level might expect to take to achieve the learning outcomes, including the assessment.

Deconstructing the Credit System

UNESCO defines a credit system as a system that provides a way of measuring and comparing learning achievements (resulting from a course, training or placement) and transferring them from one institution to another, using credits validated in training programmed.

CEDEFOP defines a credit system as an instrument designed to enable the accumulation of learning outcomes gained in formal, non-formal and/or informal settings, and facilitate their transfer from one setting to another for validation and recognition.

A credit system can be designed by describing:

- An education or training programme and attaching points (credits) to its components (modules, courses, placements, dissertation work, etc.), or

- A qualification using learning outcomes units and attaching credit points to every unit.

This helps educational institutions to organize their study programmes whereby both credit accumulation and transfer, facilitate lifelong learning and access to workplace training. In the Indian context, the definition by the CEDEFOP is more relevant given that a large proportion of people entering the labour market may not be having formal training or formal education but have gained skills and knowledge which can be validated and recognized with the help of the credit system.

The credit accumulation therefore would include skill training, experiential learning and academic education. This would help them in continuous learning and provide them with mobility pathways. In developing a holistic credit framework, we can look at both national and international models.

National models of Credit

- Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) by UGC is being implemented in several universities across the States/UTs.

- Skills Assessment Matrix for Vocational Advancement of Youth (SAMVAY) credit framework is functioning in the community college scheme for Diploma (Voc) courses.

In both CBCS and SAMVAY, theory, practical and experiential learning are awarded credit points. The B.Voc system provides multiple entry and exit and weightage are given to both general and skill components. The basic principle for allocating credit is successful assessment.

- Academic Bank of Credit: The NEP, 2020 proposes to establish an ‘Academic Bank of Credit’ (ABC) which could digitally store the academic credits earned from recognized institutions so that the degrees can be awarded taking into account credits earned at various levels. The bank has already been inaugurated by the Honorable Prime Minister.

International Models of credit

- Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF)

- Sri Lanka Qualification Framework (SLQF)

- European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System

Also read: National Training Fund (NTF): A Vehicle for Convergence – https://nationalskillsnetwork.in/national-training-fund-ntf-a-vehicle-for-convergence/

Constraints to be addressed

- Defining credit value for various levels of formal education and technical education for accumulation and transfer especially in India where there exists diversity across school boards and also levels of higher education; pedagogy and curriculum variation.

- The dilemma of focusing on duration or depth of course or both for assigning credit values.

- Defining time duration for achieving a particular competency

- Providing credit to experiential learning and mapping it to NSQF

- Mapping of ITI courses with the higher education system and NSQF

- Progression from short term courses to schools, given short-term courses do not have well-defined progression pathways. While the credit framework can be designed theoretically, implementation needs to be monitored. It may face problems in actual implementation.

In this regard it’s worth mentioning that in 2016 to break the barriers between formal education and skill development, an MoU was signed between the Directorate General of Training and NIOS under the Ministry of HRD (now, Ministry of Education) for putting in place a system for academic equivalence to vocational/ITI qualification, thereby opening options to meet aspirations of those candidates of ITI system who want to attain a high academic qualification in addition to their skills.

This MoU also opens pathways for ex-trainees of ITI, holding National Trade Certificate (NTC) to earn secondary/senior secondary qualifications.

- Establishing ITI and NIOS equivalence at various levels of school education

- Possibility of bundling SSC courses to give equivalence with long term ITI programme and ensuring progression to vocational courses in academics (B. Voc).

However, the progress has been very slow.

Ms. Sunita Sanghi, Ex Principal Adviser MSDE. She has developed and initiated numerous policy interventions in the areas of education and skilling while working with Government of India, such as National Skill Qualification Framework (NSQF), Credit policy for TVET and Aspirational Districts Skill Abhiyan (ASA), etc.

Dr. Gagan Preet Kaur is working as Urban Skilling Specialist with Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. She is development professional with over 11 years of experience in education, skill development, capacity building and environment.

(The views expressed in the article are personal and do not reflect the views of the Ministry).